The Moving Picture Revolution: Google's Veo 3 Reshapes Video Creation

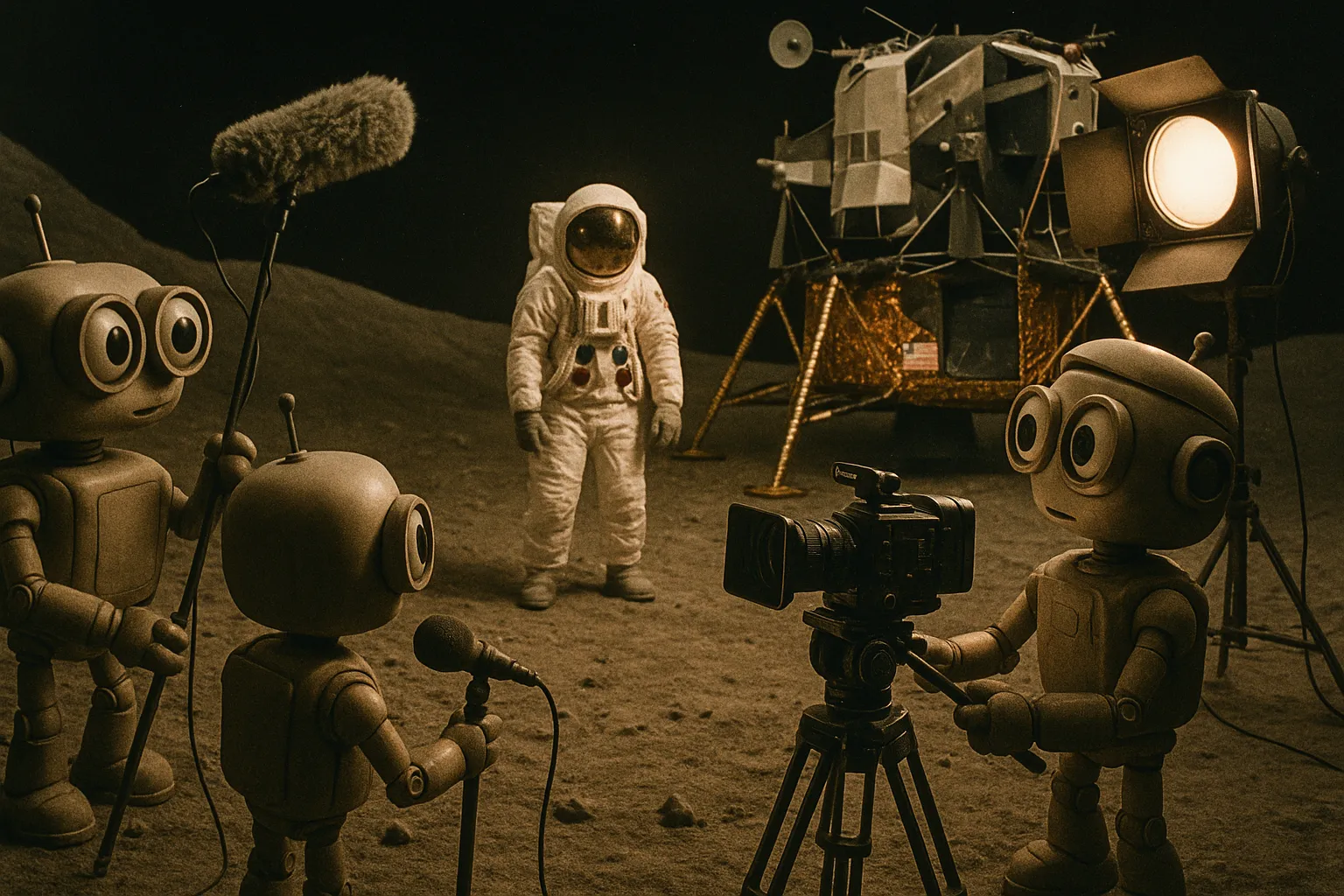

In the annals of technological disruption, few innovations arrive with the quiet confidence of inevitability that characterises Google’s latest venture into artificial video generation. Veo 3, the third iteration of the tech giant’s video synthesis model, represents not merely an incremental improvement in machine learning capabilities, but a fundamental reimagining of how moving images are conceived, created, and consumed. Like the printing press before it, this technology promises to democratise a medium previously reserved for those with substantial resources and technical expertise.

The significance of Veo 3 extends far beyond its impressive technical specifications. Where previous generations of AI video tools produced clips that betrayed their synthetic origins through telltale glitches and uncanny movements, Veo 3 generates footage that approaches photorealistic quality. The model can produce videos up to one minute in length at 1080p resolution, responding to text prompts with remarkable fidelity to both literal descriptions and subtle stylistic cues. Perhaps more remarkably, it demonstrates an understanding of physics, lighting, and cinematographic principles that would impress seasoned directors.

The architecture underlying Veo 3 builds upon transformer technology, the same foundational approach that revolutionised natural language processing. However, adapting these principles to video generation presents exponentially greater challenges. Where text models must consider sequential relationships between words, video models must simultaneously account for spatial relationships within frames, temporal consistency across frames, and the complex interplay between motion, lighting, and perspective that creates believable moving imagery.

Google’s approach involves training the model on vast datasets of video content, teaching it to understand not merely what objects look like, but how they move, interact, and respond to environmental conditions. The model learns that water flows downward, that shadows shift with light sources, and that fabric behaves differently from metal when subjected to wind. This understanding emerges not from explicit programming but from pattern recognition across millions of hours of footage, creating an AI system that has effectively absorbed decades of human knowledge about visual storytelling.

The technical achievement becomes apparent when examining Veo 3’s capabilities in detail. The model can generate coherent camera movements, from smooth pans to complex tracking shots that would typically require expensive equipment and skilled operators. It understands cinematic concepts such as depth of field, maintaining focus on subjects while artistically blurring backgrounds. Most impressively, it can maintain character consistency across cuts, ensuring that a person described in the initial prompt retains their appearance and clothing throughout a sequence.

These capabilities position Veo 3 as a potentially transformative force across multiple industries. The entertainment sector, traditionally resistant to technological disruption due to its reliance on creative talent and established workflows, finds itself confronting a tool that could fundamentally alter production economics. Independent filmmakers, previously constrained by budgets that precluded elaborate special effects or exotic locations, can now generate Hollywood-quality sequences from their laptops. The implications for advertising are similarly profound, as agencies can rapidly prototype concepts, test multiple creative directions, and produce finished campaigns without the logistical complexity of traditional shoots.

The educational sector presents another fertile ground for disruption. Textbook publishers and online learning platforms can now illustrate complex concepts with custom animations, bringing abstract ideas to life in ways previously impossible within reasonable budgets. Medical schools can generate anatomical visualisations, history courses can recreate historical events, and language learning applications can create immersive cultural scenarios tailored to specific pedagogical objectives.

Perhaps most significantly, Veo 3 democratises video production in ways that echo the broader technological trend toward accessible creation tools. Just as smartphone cameras transformed photography from a specialist pursuit into a universal form of expression, AI video generation could make sophisticated moving image creation available to anyone with an internet connection and imagination. This democratisation carries profound implications for how stories are told, whose voices are heard, and which perspectives shape our visual culture.

The technology’s potential extends beyond mere content creation into the realm of rapid prototyping and conceptual development. Architects can generate walkthrough videos of proposed buildings, product designers can demonstrate functionality before physical prototypes exist, and marketers can test consumer responses to different visual approaches without incurring production costs. This acceleration of the creative process could compress development cycles across numerous industries, enabling faster innovation and more experimental approaches to visual communication.

However, the disruptive potential of Veo 3 brings corresponding challenges that society must navigate thoughtfully. The technology’s ability to generate convincing footage of events that never occurred raises immediate concerns about misinformation and the erosion of visual evidence as a foundation for truth. While watermarking and detection technologies are being developed alongside generation capabilities, the arms race between creation and detection tools seems destined to be ongoing.

The economic implications for creative industries are similarly complex. While Veo 3 enables new forms of creativity and reduces barriers to entry, it simultaneously threatens traditional employment models within video production. Camera operators, lighting technicians, and location scouts may find their roles evolving or, in some cases, becoming obsolete. The industry must grapple with how to harness these capabilities while preserving the human elements that give visual storytelling its emotional resonance.

The competitive landscape surrounding AI video generation suggests that Veo 3 represents the opening salvo in what promises to be an intense technological rivalry. Companies across Silicon Valley and beyond are racing to develop comparable capabilities, recognising that dominance in this space could reshape everything from social media platforms to streaming services. The winner of this competition will likely influence not merely which tools creators use, but how visual culture itself evolves in the coming decades.

Legal frameworks lag behind technological capabilities, creating uncertainty around intellectual property, liability, and regulatory compliance. Questions about training data usage, copyright implications of generated content, and responsibility for harmful outputs remain largely unresolved. The legal system’s response to these challenges will significantly influence how quickly and broadly the technology is adopted across different sectors.

As Veo 3 and similar technologies mature, they point toward a future where the distinction between “real” and “generated” video becomes increasingly meaningless for practical purposes. This evolution mirrors broader trends in artificial intelligence, where the focus shifts from whether machines can replicate human capabilities to how society adapts to ubiquitous artificial competence. The question is no longer whether AI can generate convincing video, but how we restructure industries, regulations, and cultural norms around this new reality.

The arrival of Veo 3 thus represents more than a technological milestone; it marks the beginning of a new chapter in human visual expression. Like previous revolutionary technologies, its ultimate impact will depend not merely on its technical capabilities but on how creatively and responsibly society chooses to deploy it. The moving pictures that defined the twentieth century may soon give way to a new paradigm where anyone can be a filmmaker, any story can be visualised, and the only limit on visual creativity is human imagination itself.

In this brave new world of synthetic media, the pen may indeed prove mightier than the sword, but the prompt might prove mightier than both.